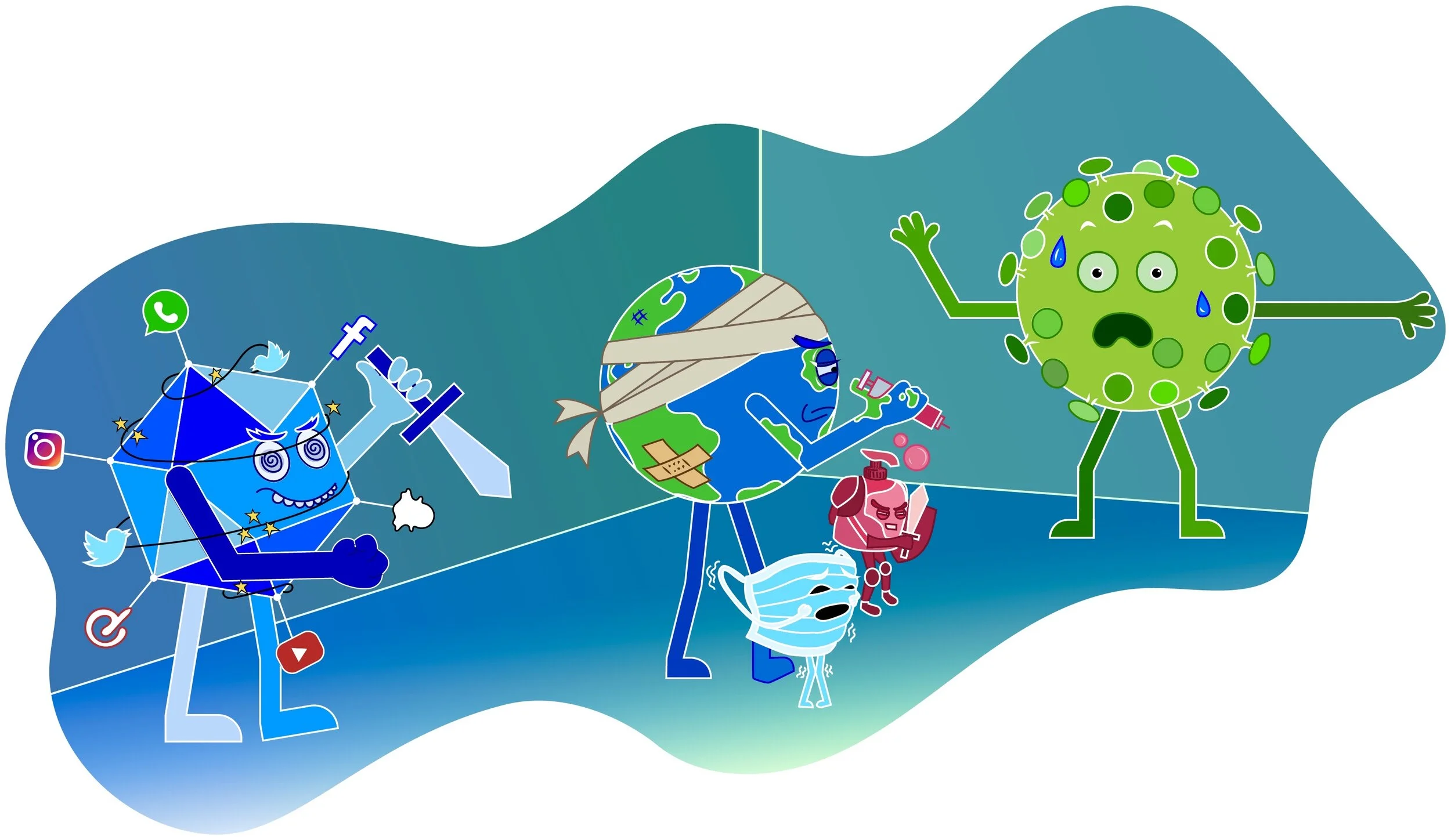

The COVID-19 Infodemic

A pandemic. Mass technology. A recipe for disaster.

5G radiation caused the Covid-19 pandemic. Hydroxychloroquine is the cure for Covid-19. The virus was genetically engineered in a lab in China. Drinking cow urine can cure Covid-19. Bill Gates wants to use a vaccination program to implant digital microchips that will track and control people. Taking six deep breaths and then coughing while covering one’s mouth will cure Covid-19. Consuming garlic, onions and turmeric prevents the virus. Covid-19 doesn’t actually exist.

“We’re not just fighting a pandemic; we’re fighting an infodemic,” said Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO’s director-general, at the 2020 Munich Security Conference. An infodemic is defined as an overabundance of information about a problem, that is typically unreliable, spreads rapidly and makes a solution more difficult to achieve. Conspiracy theories, disinformation and misinformation have become highly prevalent in the age of social media and have skyrocketed since the beginning of this pandemic. After all, with the increasing openness, access and prevalence of the internet, anyone can churn out new and often unreliable content.

The ability of fake news to spread like wildfire has been proverbial for centuries: “Falsehood flies, and the Truth comes limping after it”, wrote Jonathan Swift, the well-known Anglo-Irish writer and prose satirist, in 1910. It’s no surprise that often fake news stories are sensationalised. In fact, many online businesses encourage production of news that is ‘click worthy’ because more clicks result in more profit through advertising revenue. But who is to blame for the rapid spread of fake news? In the 21st century, there are three major culprits – microtargeting, bots and people like us.

Microtargeting is where websites use tracking cookies to collect and analyse people’s web usage and then deliver this to social media analytics firms. This data is used to predict their interests and purchasing patterns to select and deliver adverts they would respond best to. In this process companies pay social media platforms in exchange for advertising their product. Issues arise because not everyone is just harmlessly promoting their products; some companies are purely trying to make a profit without even considering the effect on consumers. A blaring example of this is the recent popularity of scam sites selling bogus testing kits, fictitious protective equipment and fake, unlicensed medications for Covid-19. Perhaps now more than ever, we require more stringent online policing.

Social media platforms have become home to millions of bots that help propagate and inflate the apparent popularity of fake news. Bots are computer algorithms utilising artificial intelligence; they work on online social network sites to execute tasks autonomously and repetitively whilst mimicking normal internet user behaviour.

According to estimates in 2017 by C.A. de L.S. Berente Nicholas, there were 190 million bots in total on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.

Bots help in the propagation of fake news due to their capabilities to search, retrieve and post non-curated content using trending topics and hashtags as the main strategy to reach a broader audience.

Now, it’s not fair to put all the blame on bots because the majority of the transmission is caused by real people. Research by Tandoc et al. shows that a positive feedback loop is created and suggests that “when a post is accompanied by many like, shares, or comments, it is more likely to receive attention by others, and therefore more likely to be further liked, shared or commented on.” These popularity indicators in social media platforms can alter the reader’s perception and make us more vulnerable to fake news.

Despite knowing this dark side to the digital world, why do people still believe the unbelievable?

Let’s face it - the human mind is a fickle thing. By being constantly deluged with medical news from numerous sources on various social media platforms, it’s inevitable to fall into a vortex of information and believe things that allow us to make sense of the turmoil of the real world. We have biologically evolved to crave answers and when there is no definitive explanation to a situation, it’s an underlying defence mechanism to settle for answers that may not even be true. After all, isn’t it better to seek comfort in hoax explanations than live in a constant void with apprehension of the unknown? Psychologists cannot pinpoint just one reason why humans fall prey to fake news, be it by word of mouth or through technology, but instead have highlighted an amalgamation of possible explanations.

The first is confirmation bias where people are lured to believe information that aligns with their personal beliefs. The second is lack of critical thinking – how many of us analyse articles that we read, question the authenticity of the presented “facts” or check the validity of the source? This ties in well with the impatient nature of humans where we often quickly scroll through our news feed and pick up on only the headlines which can make their way into our subconscious. Furthermore, health information has the ability to be amplified or drowned by celebrities’ views as the public respect their opinion, maybe even to a greater degree than health professionals. Also, reiteration of the same news several times is a key strategy used to embed ideas into the minds of people. Lastly, people’s emotions are targeted.

Fake news can evoke and breed vehement emotions which can make the audience think less rationally hence making them more susceptible to believing.

It’s universally acknowledged that fake medical information can have devastating consequences. The infodemic is not only fuelling mistrust and doubt towards the healthcare system and the government but is also causing people to be confused as to what they should and should not believe. In times where social cohesion is essential, fake medical information is promoting polarised views which is creating a fragmented society from 5G phone masts being set alight to frustrated anti-lockdown and anti-vaccine protests with some claiming that the virus is a hoax.

Tough times make people vulnerable and a glimmer of hope like Covid-19 medications or miracle “cures” being sold by online scam companies encourage people to take a leap of faith. However, situations like these have the potential to go horrifically wrong – participating in any unproven drugs or “cures” e.g. inhaling disinfectant, consuming hydrogen peroxide, drinking colloidal silver solution to name a few can damage the health of individuals and in some cases be fatal. One example of this is in Iran where methanol, which is acutely poisonous, was claimed to be a cure. This resulted in a significant escalation in methanol related morbidity and mortality in Iran with 728 deaths after ingesting toxic methanol compared to only 66 in the previous year. Other shocking scam cures include a $300 “vaccine” comprising of a mix of amphetamines, cocaine and nicotine and a $14990 device called the Biocharger NG Subtle Energy Platform which Australian celebrity chef, Pete Evans, claimed could cure coronavirus.

So how can we differentiate between what medical material is genuine and what isn’t? When inspecting a piece of medical information, critically analysing the source’s intentions will help to identify the trustworthiness of the information. Mainstream news outlets, websites and organisations with good reputations e.g. BBC, The BMJ, The Guardian, NHS websites aim to keep the public informed with accurate information. The same cannot be said for some companies who mould facts to fit their argument to portray themselves in the best possible light in order to make a profit. If an article claims to reveal something that your “doctor will not tell you about”, it is an immediate red flag. Furthermore, don’t rely on social media platforms for medical news because anything can be shared on there as there is no filter to keep disinformation and misinformation at bay.

Articles making sweeping conclusions that are not supported by solid evidence should not be trusted. It’s crucial to realise that the bigger the claim, the more evidence is required. If it’s a massive breakthrough, it will have been tested on thousands of patients, published in major medical journals like The Lancet, BMJ, The New England Journal of Medicine and covered by the biggest and renowned media organisations around the globe. If the article says that the research has been published in a particular journal, check online whether the journal is peer reviewed – this means whether it has been heavily scrutinised by scientists in that field before publishing. Also, when coming across medical news, don’t stick with just one source, check whether other sources have presented similar findings.

Lastly, if a study was sponsored by the pharmaceutical, supplement, or device industry that is peddling the product under review, the information may be biased so always be alert.

At this moment, we are living in a world that we could not have imagined. The virus threatens billions of people worldwide and tackling it should be the priority. However, let us not turn a blind eye to the fact that humanity is not just fighting one enemy but two, one which stands towering in the spotlight and the other which lurks behind our backs.

Top 5 tips to avoid fake medical news

Develop a critical mindset and question the writer’s intentions.

Ensure that the source is a reputable, trustworthy organisation.

Don’t rely on social media platforms for medical information.

Look out for strong scientific evidence for any big claims and check if other reliable sources have got similar findings.

Keep your eyes peeled for any “sponsored content” within articles.