What do we owe to each other? Part 2: Deontology

It has been almost a year and two months since the critically acclaimed (by my mum) first part of this crash course philosophy series was published.

And although we have had not one but three lockdowns thanks to the efforts of our dear leader and his loyal lackey, I have managed to procrastinate this, the second part of the ‘What do we owe to each other’ series, until today, only a few weeks before my next ICA.

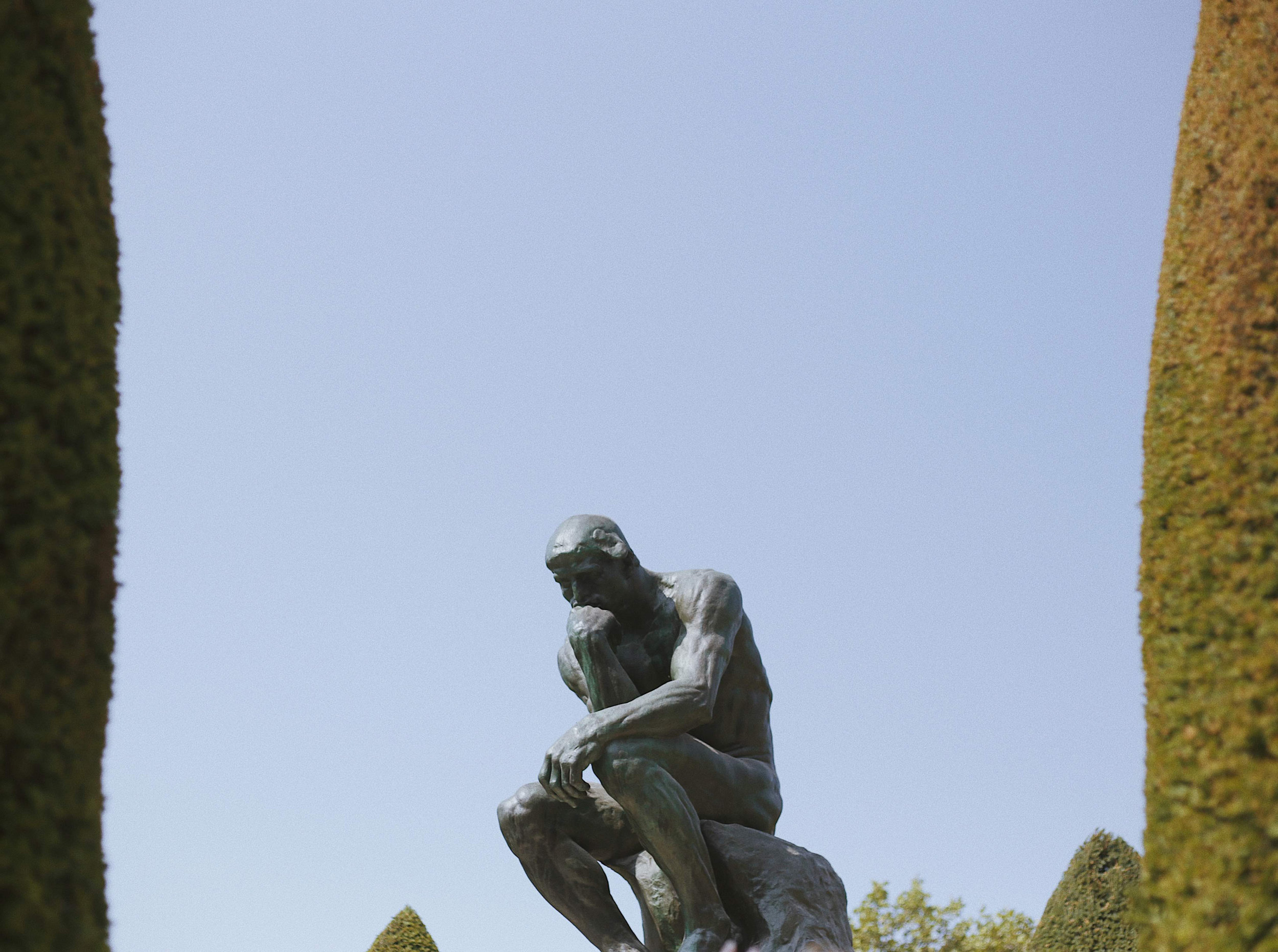

Regardless, the question is one, we as a country, have had to ask ourselves throughout this time of personal sacrifice. It has been, I hope, a time of reflection and a time for thought. As future medical professionals, I have expressed in the previous part, the importance of the privileged position we will find ourselves in and the impact of our choices on the people we treat. And sometimes those choices will yield unexpected and perhaps unwelcome outcomes.

In the previous part, I talked about Utilitarianism, a consequentialist philosophy that would provide no refuge to you ethically in the case the outcome is pernicious or downright detrimental.

Deontology, however, has your back. In many ways it can be thought as the direct opposite of consequentialist ethics. In Deontological theories, the reason and motivation behind your actions, rather than the consequence of the outcome, are the most important when determining the morality of the action. So, if for example, you donated £100 to a charity because you wanted to help and support the cause, that would be morally righteous according to Deontology. But if the intention was to embarrass someone else by donating more than them, then as the intention is morally questionable, the action would be deemed wrong, despite the outcome being the same.

Now even if you have just skirted the periphery of philosophy, you will no doubt have heard of one of the giants of the enlightenment, Immanuel Kant. And if you have not, congratulations on having a social life in senior school rather than gawking at the sheer audacity of enlightenment thought in the historical context.

Kantian ethics are foundational to deontological philosophy. Bear in mind that there are other theories within the deontological school of philosophy, but we will focus on Kant, as it provides a good basis with which to explore the others if you so wish.

Kant argues that the highest good must be both good in and of itself and good without qualification. The former can be achieved if it’s “intrinsically good”, and this itself is based upon moral absolutism, the idea that there is an absolute right and wrong in the world. The latter, only if the addition of that thing in any situation, will never make it ethically worse. An example where a thing may fall short is pleasure. In of itself, it is good, but it is not good without qualification, as there are people who can feel pleasure at the suffering of others, which is an ethically abhorrent situation. He therefore concludes:

“Nothing in the world—indeed nothing even beyond the world—can possibly be conceived which could be called good without qualification except a good will”

With this startling revelation, you may well be thinking, what is considered good will? Well do not fret, my boy Kant has got you: a person can be deemed to have good will, if their action respects the moral law. Kant constructs this moral law using the central idea of the categorical imperative, which has three significant formulations:

Act only according to that maxim (i.e., your will and intent) by which you can also will that it would become a universal law.

Act in such a way that you always treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never simply as a means to an end, but an end in and of itself.

Every rational being must act as if he were through his maxim, always a legislating member in a universal kingdom of ends.

Properly explaining and expanding on these formulations would turn this medical school magazine article in to a philosophical magnum opus for which I have neither time, word count nor intellectual capability to concisely explain, and that is forgetting about other Kantian ideas, such as perfect and imperfect duties and the formulation of autonomy among others; the man was either a genius or, much like all enlightenment thinkers of the age, getting absolutely smashed on caffeine, it’s probably a combination of them both.

The main idea here is that if a person’s maxim, became a universal law, would it be morally right and just? The only absolute good is goodwill, so the determining factor as to whether an action is right, is through the will/ motive of the person.

Despite the intricate concepts, backed up by a coherent albeit reasonably debatable line of logical reasoning, it should not be too hard to see the issues with this rigid school of thought. There are many critiques out there of the entire school of deontological thought and Kantian ethics with its categorical imperative, and no, that is not just from sore consequentialists and the bad boys of the philosophical world.

In the first part of the series, I asked you to consider the trolley problem and the organ transplant variant with the eyes of an avid Utilitarian, to see how that philosophy can be applied in difficult moral situations. I would now ask you to re-consider those same problems with the eyes of a Deontologist and Kantian. Would the actions be different? Are they morally justified? Is one situation ethically superior to the other depending on your school of thought?